Dear Mr Smith,

I was thinking of all the destructive dictators to take power in the 20th century, and as far as I can ascertain, few come close to the level of insanity as Pol Pot. Throughout the 1970s, Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge waged war across Cambodia, took control of the nation, and turned the once diverse country into a communist dystopia that destroyed a quarter of the population. After seeing the film The Killing Fields once again, I was inspired to do some digging and write about this insanity of the 20th Century.

AMERICAN INVOLVEMENT

A common theme amongst historians when discussing the rise of the Khmer Rouge is the illegal, and initially covert, bombing of Cambodia during the Vietnam War. The US military noticed that Viet Cong troops were mysteriously appearing in South Vietnam. With further research it was discovered that the Viet Cong had been using networks across the Cambodian border (a big theme in the film Apocalypse Now). In response to this, the United States began a secret bombing campaign of suspected Viet Cong outposts and supply lines outside of Vietnam, this would become known as Operation Menu.

While this massive bombing campaign had negative impacts on many Cambodians, was it responsible for the rise of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge? The answer is yes and no, with an important emphasis on no. The American intervention into Cambodia may have acted as the last straw, or perhaps an amplifier for the rise of an already insane dictator and his hand picked Marxists henchmen.

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Given his persona, it would not be too far fetched to imagine Pol Pot and the other leaders of the Khmer Rouge as nothing more than disgruntled farmers who took matters into their own hands. In actuality, this couldn’t be further from the case.

Born into a wealthy family in French Cambodia, Pol Pot (originally Saloth Sar) was an intelligent young man who - thanks to his family - was able to attend many elite schools across Cambodia, and later travel to Paris as an exchange student in the 1940s. It was during his time in Paris that Pol Pot would discover a deep catalogue of Marxists literature, which he spent his time absorbed in, and found a particular fascination for the writings of Stalin. He would later join several Communist organisations in France, where he would be offered many unique opportunities to learn from French and East European intellectuals.

This is often left out of history, and so too is Pol Pots close connection to Khiea Samphan - an economist from Cambodia who also travelled to Paris where he became a Communist - who would later return to Cambodia and serve as Pol Pots henchman. Samphan - like Pol Pot - was given the opportunity to study at the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris in 1950.

PLANS IN THE OPEN

While studying for his PhD, Samphan not only became an active Communist around Paris, but found himself within a circle of Khmer intellectuals who had Marxist ambitions for Cambodia. This group was known as the ‘Cercle Marxiste’, and would become influential in more mainstream French socialism in the 1950s (such as influencing the This would influence Samphans own studies. He would turn his doctoral thesis in this same direction; titled ‘Cambodias Economy and Industrial Development’, the thesis highlighted the economic lacking of Cambodia, and the need for massive reforms. It was heavily based on Dependancy Theory and Marxist-Leninism, advocating for a reformation of Cambodia into an agricultural nation, which would be spurred on by the labour of ‘city dwellers’.

While this was happening, Pol Pot was becoming increasingly radical. He had begun reading Mao, and his understanding of Stalin was deepening. Aided by other foundational socialist thinkers such as Rousseau, he was attempting to construct a grand vision; how does one achieve revolution followed by a reset? His ideas would later merge with the post revolutionary vision of Samphan to create the Khmer Rouge’s Communist plan for Cambodia.

In 1950, Pol Pot and a group of 18 other Cambodian students were allowed to travel to Yugoslavia, where he worked as a labourer and formed close connections with other communist thinkers.

This time in Europe was a shadow of things to come; already the Khmer circle were silencing those they deemed ‘counter revolutionaries’, while also strengthening a unique ideology that could be transported back to Cambodia and applied to the people.

RETURNING AS REVOLUTIONARY

From the time of Pol Pots return to Cambodia in 1953, through to 1970, the Cambodian government underwent various political struggles and changes. Pol Pot himself would become a member of Cambodian arm of the Viet Minh (the Khmer Viet Minh) and join in the fight against Cambodian leader Norodom Sihanouk. This Marxists assault of the government was taking place over a decade before Operation Menu devastated the border region of Cambodia and Vietnam.

Following a series of setbacks and internal problems in the early 1960s, the Viet Minh retreated back into North Vietnam. At the same time, Pol Pot helped reorganise the Kampuchean Labour Party into the new Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), and in 1963 began another war against leader Sihanouk. This would once again fail.

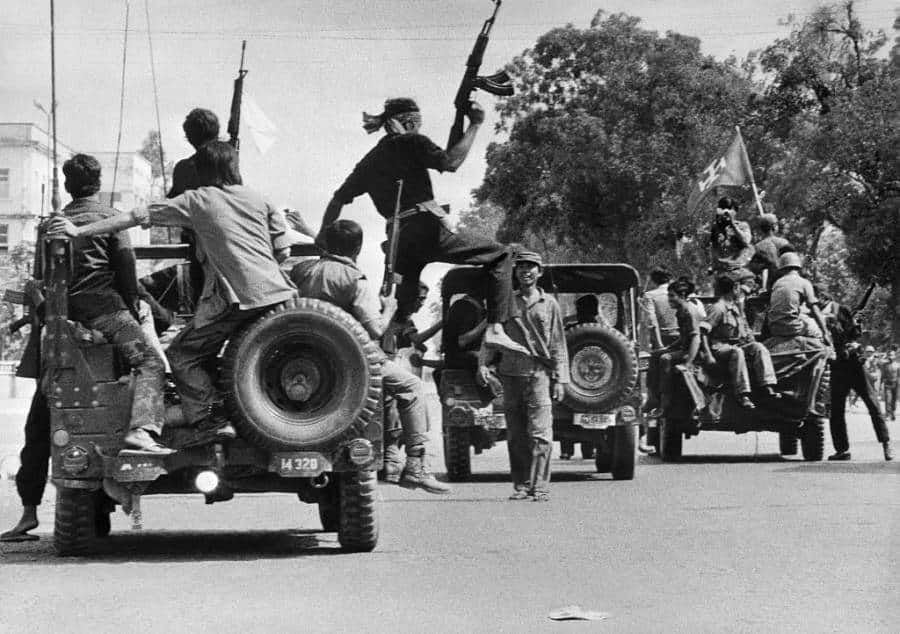

It would not be until 1970 that the Khmer Rouge would rise. With a US backed government now in power, Sihanouk was expelled, and the CPK got to work organising a rebellion. The Cambodian Civil war would follow, and continue throughout the early 1970s, with the Khmer Rouge often defeating the American backed Cambodian government forces thanks to external support from North Vietnam.

COMMUNISM ESTABLISHED

After years of fighting, in 1976, Cambodia would fall under the leadership of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge’s new government; the Democratic Kampuchea. This violent time would act as a testing ground for the many Marxist ideas espoused by the French intellectuals almost two decades earlier in Paris. The many original Khmer students were given positions of power in the Khmer government.

The goal was simple; Cambodia must undergo a ‘great reset’. Using Pol Pots unique Nationalist-Stalinist ideas as a basis, everything from Cambodian history to the existence of cities and sunglasses was to be destroyed. History was to be completely reset, and a ‘year zero’ was announced. Of particular interest to Pol Pot were urbanites, who he saw as parasites guilty of ‘soft living’ and therefor a threat to the Marxist ideal. The cities were emptied out (as cities do not produce goods but trade them, something which contrasts ‘to each according to his own’) and the populations were sent to the fields to produce.

With everything centralised, the Cambodian government starved or deliberately murdered up to a quarter of their population.

THE GREAT RESET

Of all the things which happened in Cambodia, none are too far from happening in the west, even today. In particular, we have seen our leaders more than willing to enter contracts that guarantee a ‘great reset’ of culture, economy, and society. This idea is not new, nor has it ever actually worked successfully.

The idea of a cultural reset - for the uninformed - is blatant Marxian theory in the open. The thought leaders behind this idea - such as businessman Klaus Schwab - may simply see this theory as an effective element in ‘bettering’ society, but history has taught us otherwise.

Immediately following the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia in 1975, a ‘year zero’ was announced. This would mark a ‘rebirth of Cambodian history’. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge leadership had long been planning such an event, which would begin with the destruction of foreign ideas, and move on to more general ideological differences. This would later be expanded in 1976 with the establishment of the Democratic Kampuchea.

The core idea - as laid out by Pol Pot, Samphan, and others - focused on the reorientation of a given society. A revolutionary class - primarily peasants - must arise and take hold of power, and all previous cultures, traditions, and even ‘memories’ of the given society before Year Zero must be erased. In Cambodia, this most famously manifested itself in the mass murder of - among others - the educated class, particularly those who had advantageous skills such as being multilingual. Nothing was untouched by these ideas, even traffic laws; driving on the left hand side of the road was made the standard (despite buses then having to unload passengers into the street), as driving on the right hand side was a “Western idea”.

For the Khmer leadership, the ideal goal was the eradication of pre revolutionary knowledge, and the elimination of ‘westernised’ and ‘corrupted’ urbanites. Khmer doctrine promoted a classless agrarian system, with the ideal Cambodian being an uneducated agricultural worker. To achieve this, Pol Pot first targeted the common thorns in the side of a Socialist system; religion was outlawed, private property was abolished, the idea of ‘family’ was labelled foreign and families were split up, and money (and by extension banking) was deconstructed and destroyed. Soon after this, all books were burnt (and likewise people with glasses were targeted, since it was a sign of education or class), and hospitals, factories and educational institutes were shut down. The results of such things as lack of hygiene meant that by 1976 (just one year after the ‘reset’ began) roughly 80% of Cambodias population had malaria.

Everyone was grouped under two labels; those who were educated, lived in urban areas, or were deemed part of a ‘non-peasant class’ were labelled ‘New People’, while peasants, the uneducated, and those who lived in rural areas were labelled ‘Old People’. The ‘New People’ were unable to own anything, forced to work at minimum 10 hours per day, and received rations which were so limited that starvation was almost certain. The Khmer Rouge motto made reference to the New People; “To keep you is no benefit. To destroy you is no loss.”

Luckily, Pol Pots time in power was limited, and his ideas were never fully realised; his destructive attempts at a Marxist reset were ironically cut short by Communist Vietnam declaring a border war with the Khmer Rouge, which ultimately forced Pol Pot and the majority of the Khmer leadership into exile.

This idea was not unique to the Khmer Rouge, in fact Pol Pot had taken inspiration from the ‘Year One’ concept established following the French Revolution. The idea of a cultural reset appears to be necessary not only in Marxian ideologies, but in any socialist ideology which seeks to control a society. The ‘old’ way of things must be removed completely if a new order is to exist. Pol Pot and Samphan’s ideology stands as an exceptionally brutal example of Communism in action, however in my opinion I believe it is simply a more complete and blunt manifestation of the socialist idea. While the Soviets and Chinese had to retract from, and ‘thaw’ out, their socialist policies in order to survive, the Khmer Rouge simply cut to the chase with devastating enthusiasm.

THE FRENCH CONNECTION

Throughout all of this, there is an important connection which needs to be highlighted, and that is between the Khmer Rouge leadership, and the French Communist intellectuals. It is evident that the French have always been open to the idea of Marxism, however this was never more so the case than in the 1940s, when the Soviet Union was still seen as a beneficial ally to the western world.

It was during this time that many French intellectuals held positions of power while being free to openly support classical Marxism (this was long before the publishing of ‘The Gulag Archipelago’, and the fallout that came with it). Many of these intellectuals were heavily involved with the Cambodian Khmer in France. Among them was Samir Amin - a French Marxist political scientist responsible for the ‘Eurocentrism’ idea - who is mentioned in Samphans 1959 doctoral thesis. Samphan admits to implementing Amins ideas and theories into his work, and as a result much of what we have witnessed in Cambodia could have been laid in part at the feet of intellectuals such as Amin.

Amin would continue to praise the Khmer Rouge far after its fall from power in 1979, and would go so far as to call it “one of the major successes of the struggle for socialism in our era” in 1981.

The French Communist intellectuals were quick to praise the plans of Samphan, Ieng Sary, Pol Pot, and the many other Cambodian revolutionaries who studied in Paris, despite the obviously destructive nature of these plans. While the Cambodian Marxist experiment would eventually be exposed as a communist hell, the French intellectuals quickly moved onto the next modernised iteration of Marxist thought; Post-Structuralist Post-Modernism. As always, the Marxist idea is simply rewrapped whenever it falls open to any criticism, and this destructive pattern continues on to this day.

With so many well documented failed attempts at the Marxist ideal you would think we would spot it a mile off and repel anything that even hints at such diabolical ideology. We look at the history of the Khmer Rouge and shudder, yet tolerate the very same moves toward a ‘great reset’ that can only eventuate in the same misery delivered by Pol Pot.

Sincerely yours,

O’Brien

Another good piece O'Brien. I hadn't thought of some of the parallels with today, but as is said .. if there's one thing we learn from history, it's that we struggle to learn from history.

An interesting symmetry between the Khmer Rouge Year Zero and the Current Year's Great Reset is that the former sought to empty the cities and starve urbanites to death working the rice fields, while the latter seeks to empty the countryside and herd the population into tenements where they can be slowly starved to death while being pacified in their VR pods.