Philosophy: Marx’s Anti-Reality

Recently I had written a letter highlighting some of the philosophy of Jean Paul Sartre. I am wondering if this urge to sketch aspects of such influential characters will become a series focusing on philosophers or philosophical ideas I am intrigued by (although not a summary of their works) to highlight particular ideas that have stood out to me - I hope you will indulge me!

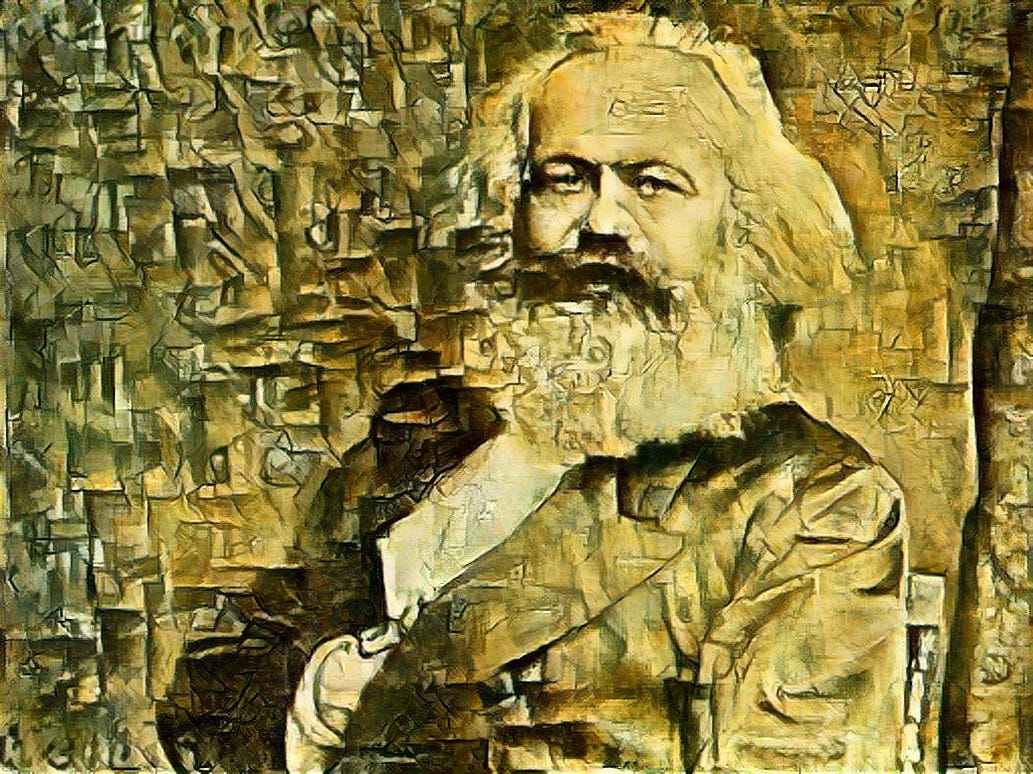

In this instant, I want to highlight a few details of Marxism which I don’t think I have touched on yet. While I am at it, I may as well say a few words about the early life and decisions of Karl Marx himself. I am mostly interested in the idea that Marx and his followers were/are part of a faith, based around what I would call ‘anti-reality’. That is to say, Marxism rejects reality both metaphorically and literally, but more on that later.

KARL MARX’ ANGST

It should come as no surprise that Karl had an interesting upbringing. While I am no expert on his early life, I am aware that his relationship with his parents was strenuous as a result of his behaviour. His parents were converts from Judaism to Christianity, and although originally open to religious ideas, the young Karl Heinrich Marx would eventually become vehemently opposed to religion following ‘mentoring’ by a supposed occultist, which I will get to later.

Karl’s father, Heinrich Marx, was of little help to him in regards to straightening out his attitude. While his mother was a true Christian, his father Heinrich was much more the intellectual than a man of faith. Heinrich privately educated Karl and likely instilled in him the teachings of Immanuel Kant (who Heinrich adored, and so too would Karl later on in his life). It is also highly probable that Heinrich brought out a revolutionary nature in the young Karl; Heinrich had been angered by the oppression of Germany's Jews following the defeat of Napoleons Grande Armée by the Prussians in 1815, just before Karl's birth, and often took part in anti-government activity which led to many encounters with the police.1

Karl eventually left home for university, where his previously close relationship with his father was loosened by his sombre anti-social behaviour, drinking, poor grades, and what his father called his ‘degeneration’. While Karl would remain fond of his father for the rest of his life, it seems as though the feeling was not reciprocated. I believe this distancing from his closest family member accelerated his already dark outlook on life.

At some point around this time, Marx began writing poems (which can still be found online) espousing his anger at the world. One such poem described his longing to both destroy the world in ‘blackest agony’, all the while building something which would cause even God himself to be taken aback.

I mention these things, because they ultimately shape an interesting picture of who Karl Marx truly was. I have seen many conspiracies surrounding Marx’s supposed ‘employment’ by secret societies in order to spread the Communist idea, accusations that point in every which way, and if there is any truth in these statements it is certainly hard to discern. What is not hard to discern is that Marx’s own life was filled with sombreness, anger, and resentment at both ‘the world’ and ‘God’, (something which I see in many younger people today actually), and which I suspect rarely ends well. I see that Marx was ‘at war with God’.

At some point Marx also (supposedly) came under the mentorship of an occultist. I say supposedly because I cannot recall the exact details, as I read this years ago, so perhaps take this with a grain of salt (if you have more insight please let me know). From memory, this particular philosophical mentor - learned in the occult - encouraged Marx to open himself up to various spiritual ideas beyond his Christian upbringing. This apparently lead to Marx’s hate of religion, and spurred on the creation of some of his darkest poems.

THE IMMUNITY OF MARX

Before jumping into some of my recent observations on the nature of Marxism, I may also briefly mention an observation of Marx’s own legacy in our time, just in case any more evidence was needed to suggest that the prevailing ideology within western institutions of education might be of Marxist origin…

As mainstream political commentator Douglas Murray was quick to notice that Marx stands alone as one of the few historical figures who has remained immune from modernities critisisms. While icons of the enlightenment and thereafter - from presidents to philosophers - have had their statues destroyed, their names pulled from history books, and their paintings labelled with ‘racism’ warnings, Marx has come under no criticism. How is it that Abraham Lincoln, who helped end the Atlantic slave trade, could be labelled a racist, while Marx remains immune?

From Marx’s letters he frequently used derogatory terms to refer to black people, he was openly anti-Semitic, and he admitted to Engels that he hoped conditions would worsen for the working class so that they would accept his ideas and revolt. In contrast to Lincoln or Voltaire, he certainly had a knack for anger-fueled ranting.

MARXISM VS REALITY

With this in mind, I should now turn to a few brief but (in my opinion) important observations of the Marxist faith I have made in recent months. Although I have been interested in the history of such things as Marxism for a long time, I am still trying to understand why it continues to propagate itself in various forms as if it’s some magic formula for life. That is, why is Marxism attractive to certain individuals on a conscious and subconscious level, despite the fact that when implimented it always ends badly for most of the people.

I should start by saying that I do believe Marx was correct in some odd way. In a broad sense, he realised that many (perhaps including himself) were disenfranchised by society in a way that seemed fundamentally unfair. This is something all too relatable today, and I think it would be safe to say throughout practically all of human history. The twist for Marx was his absolute willingness and drive to ‘take back’ the scales that mediate absolute fairness between people. I am convinced that such a blatant worldview is attractive to the disenfranchised, particularly to those who believe they are bound to suffer under difficult circumstances.

The difference between Marx and those who preceded him in the sphere of ‘proto-communist’ writing was his ability to claim the ‘scientific method’. Before Marx and Engels many such philosophical writers were obsessed with ‘abstractions’. One such writer (his name escapes me) had influenced Engels and perhaps planted the seed for the Communist Manifesto in Marx’ head, however his theory was based on absurdist beliefs such as the earth and the planets being ‘living beings’ which would create children, and that the utopia would only arrive after an esoteric planet-joining event brought about by socialist-minded individuals on earth. Engels said that this particular writers ideas were good, but lacked the so called scientific method that would eventually be present in the Communist Manifesto.

What Marx and Engels did in their ‘scientification’ of socialism was take existing ideas and merge them with ‘economic’ observations of the time, in order to add a layer of credibility to their work. Of course, Marx was not an economist, despite the fact that his ideas were presented as some sort of economic fact. I believe - as do many others - that Marxism disguised itself under a veneer of ‘economics’. In my mind it is something more akin to a set of sociopolitical ideas wrapped in pseudo-economics. This is important to consider, since many of the propositions of Marxism do not hold true - not only in practice but to some extent even in theory.

For example, Marx built a large portion of his theory around the false premise that labour equaled value. Both the Bolsheviks and the Nazis would share this belief. Indeed, it seems to popular amongst most collectivist societies. It is a convincing idea, until one actually thinks about it. If labour equaled value, then value would be overabundant in Africa and South East Asia. It is not. Whether or not this mattered to Marx himself was irrelevant, since it only served as the veneer, under which was the principles of social revolution. As we see today, this radically oversimplified view of socioeconomics sufferes little resistances among university students and activists because - in my honest opinion - they, like Marx, do not actually go outside and observe reality. They would argue that labour not equaling value is a result of capitalist and imperialist systems exploiting these hard working Africans and South East Asians, despite the fact that prices were not dictated by some ‘capitalist god’ but rather by the free market.

So Marx used economic claims to justify an idea which would have otherwise suffered a swift death in the face of an ever-advancing 19th century Europe. In my opinion Marx - whether he was conscious of this or not - took age-old revolutionary ideas and co-opted the language around them in order to accommodate them in science-centric 19th century culture. The fundamental goal of Marxism was revolution. For Marx this meant instilling a revolutionary spirit (consciousness) within the proletariat. For later followers of Marx, this would shift into the realm of race politics, gender, nationality, and so forth. Ultimately the idea was not grounded in any scientific sense, since doing so would not only prove much of its core ‘facts’ wrong, but solidify it in a particular time and place - the idea must be allowed to shift, to fit into the current culture, and that includes finding new victims, new oppressors, and new methods of achieving revolution.

BREAKING REALITY

I do believe that much socialist thought since the time of Marx have been ideas set against reality (perhaps this could be called ‘anti-truth’). That is, many Marxian-based socialist ideas are built around an intrinsic hatred for the way ‘things happen to be’, and seek to destroy them or justify their inversion and abolition as the answer to social woes. I am not saying that Marxists are conscious of evil intent, or with a conscious drive for destruction and chaos. What I am saying is that I believe a large portion of those who staunchly defend the Marxist faith are of the belief that the world must change on a fundamental level which cannot be achieved with mere politics and policy. Instead, it must be an economic, social, and spiritual reset.

Critical Theory - thanks in large part to Herbert Marcuse - finally put these exact thoughts to paper. He believed (or at least claimed he believed) that society was intrinsically wrong. Working class America was finally happy, and no longer a potential revolutionary class. Marcuse claimed that these people were not ‘truly’ happy, but living in a false sense of joy. Many of the Critical Theorists (Marcuse included) also believed that the current consciousness limited ones ability to envision utopia, thus utopia became inconceivable to the masses. So it becomes pointless to clarify the utopia with specifics (as you would normally do when planning for the future…) since our pre-revolutionary consciousness limits our ability to comprehend it. Despite the non-specificity of the desired utopia, the current system is completely broken, needs to be completely pulled down, we need to start again. By this logic, and by the words of many Critical Theorists, the only way forward is to completely overturn every element of the existing society. Out of the destruction the phoenix will rise.

This is ultimately the ‘breaking of reality’ that I believe Marxism as a whole attempts to achieve, whether or not they adhere to Marcuse’ specific doctrine of raising a Critical Consciousness. In this way, it is a religious idea built upon faith in something which is unknowable. Similar to the Christian idea of a new heaven and earth, the Marxist faith seems to rely almost completely on a type of blind faith. The hope seems to be the alleviation of all constraints, made possible by escaping reality.

I must also mention that I have heard arguments from many classical Marxists (who come across as surprisingly normal) who stand against identity politics, Critical Theory, and much of modernity, instead sticking to classical (or ‘vulgar’) Marxism. They are the puritans of the faith. Despite their puritan aspirations their social sensibility, which underwrites much of their economic critique, is still fundamentally wrong, and will not solve anything.

MARX VS GOD

Social critic James Lindsay has highlighted something similar to what I have noticed in my own study of Marxism. He elaborates on what I’ve said earlier, that Marxism is a socio-religious ideology disguised within an abstracted version of the ‘scientific method’. Its adaption to the modern age does not ultimately change its fundamental goals of revolution.

From Lindsay's (very well informed) perspective, Marxism begins to make better sense when viewed not as a development of older socialist economic ideas, but as a modernised form of Gnosticism. I was particularly intrigued by this idea. Just as the Gnostics believed that ‘God’ was an evil ruler disguised in inherent goodness, and that the world (or our current ‘reality’) is a prison we must escape, so too does Marxian thought. The idea being that material suffering is proof of inherent corruption of current reality and the only ‘solution’ lay in finding its inverse. Some Gnostics believed - and I am heavily paraphrasing - that Lucifer and Jesus were bringers of knowledge, attempting to free humanity (or at least enlighten them) from their ‘prison reality’, in which they were kept by the ‘evil god’ described in the Torah and Old Testament.

Just as how Marxism portrays material inequalities as signs of an inherently corrupted reality, the Gnostics painted the Old Testament God as a tyrant keeping humanity hostage. Gnosticism - as with Marxism - seems to come to its conclusions by making abstract connections based around the precondition that things should be ‘fair’ (presuming that ‘fairness’ is somehow equilateral with ‘goodness’). Gnosticism posits that only an unfair God would withhold knowledge from Adam and Eve. Marxism believes that inequality is injustice rooted inside reality. Both believe in the establishment of a utopia on earth by human hands, and that ‘God’, ‘reality’, and the ‘systems that be’ are set in place to oppose and limit our ability to realise this utopia.

In this way, I do believe that Marx - as with the Gnostics and their child-ideologies - had the goal of fighting a ‘war against God’ based on the preconception that reality itself is a type of curse. As I mentioned, Marx was (despite hating religion) of a ‘religious mind’ in his poetic dislike of God and his own life, so perhaps Marx himself was consciously aware of this. For the majority of his followers since, I do not believe that many are of the same religious mind, but Marxian thought may be playing into a subconscious drive to see something ‘beyond reality’ manifest (yet ironically limited to material reality rather than the spiritual).

This is more than mere speculation in some sense. Marx openly stated that he was ‘at war with God’, alongside other such delightful comments as his soul being ‘committed to hell’, and his intention of luring people with him into hell. Perhaps these could be written off as philosophical anecdote, or perhaps it was a literal description of both his driving force, and an extension of his bleak outlook on life.

A final observation on this Gnostic-like attitude of Marxism - made by James Lindsay, not me - is the semblance of Marxian thought to the Genesis story. Marx believed that the consciousness required for the revolution (and thus utopia) required us to view ‘man-in-himself’. That is, a refocused idea of ourselves in relation to reality - as true independent beings and masters of our own destiny (perhaps why many new age and satanist belief systems are started by Marxists). Marx was not afraid to admit this either, stating that “Man made God in his own image”. As Lindsay notes, this is like the promise made in the garden by the Serpent in Genesis. As the story goes, it didn’t end well, and regardless of ones interpretation or beliefs in relation to the Hebrew Bible, there is no denying that attempting ‘to be gods’ always leads to problems, limitations (ironically) and ultimately destruction.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Soviet mathematician Igor Shafarevich (in his essay The Socialist Phenomenon) highlights the similarities of Marxism and broader utopian-based socialist ideas with a sort of religious and deep subconscious drive. He believed that utopian socialism was not unique to a single culture or time period, but rather the manifestation of a subconscious desire (which he believed was the Thanatos, or death drive) which both presented itself as an escape from reality and an end to suffering. As he points out, Marxist ideas are based around a rejection of the spiritual and a blind reliance on the material world as the source of, and fulfillment of, all desires. This belief likely stems from the fact that material indifference often leads to suffering, and thus if material prosperity was bought about, then the suffering of reality would be nullified.

Shafarevich notes that this is untrue, as no utopian idea can fulfill desires which inevitably exist beyond the material world. Having a never ending abundance of food does not lead to the alleviation of earthly suffering. As he notes in the essay, even if the ‘utopia’ was achieved in full, it would inevitably lead to human extinction, and even posits that perhaps that is the driving force behind its popularity in the 20th century; if the material world is all that there is, then perhaps the logical end goal is to simply die and end all suffering and striving for meaning.

I am in agreement with Shafarevich’s observation, which has since been made by many other critics of utopia-oriented socialist ideas. These ideas that attempt to break reality in exchange for utopia are bound to fail. A blind focus on the material world is a binding to disappointment. This fits in well as a contrast to the Biblical idea that “man does not live on bread alone”. Man must reject his self-convinced binding to the material nature ‘of things’, and accept that there are higher ideas that exist both beyond the individual and society. I believe that through the discovery of these ideas comes a clarity that cannot be found in materialistic doctrines such as Marxism.

Sincerely yours,

O’Brien

A note from York Luethje

Side note: Heinrich Marx did not frequently clash with the police, quite the opposite. He had to change his surname from Levy to Marx under French occupation but could otherwise practice freely as a lawyer. When Trier become Prussian in 1816 he had to convert to Christianity to continue in his occupation. This does not appear to have been an issue for him because he saw himself firmly in the Enlightenment tradition, hence his veneration for Kant. He later headed the lawyer’s guild in Trier and got bestowed upon him the fairly senior title of Justizrat. Heinrich Marx was as establishment as they come.

O'brien should know that REAL Marxism has never been tried before. My queer studies professor told me so. When we do it after the coming revolution, we'll do it right this time. (raises fist. pretends to be handcuffed.)

I think O'Brien gives old Karl more credit than Karl is due. Marx was a shallow third rate materialist socio-philosopher. His appeal is to similar shallow "thinkers".

I think O'Brien sums it up best when he wrote:

"blind focus on the material world is a binding to disappointment. This fits in well as a contrast to the Biblical idea that “man does not live on bread alone”. Man must reject his self-convinced binding to the material nature ‘of things’, and accept that there are higher ideas that exist both beyond the individual and society. I believe that through the discovery of these ideas comes a clarity that cannot be found in materialistic doctrines such as Marxism".

As to the comparison to gnostics I think that is way off. Gnosticism is not one shared common belief. There was quite a bit of diversity. The concept of god being evil was not that God is evil but rather the false god of the material world (or I should say imagined material world) ...the demiurge was the baddie. And very similar to what O'Brien says .....man must reject his self convinced binding to the demiurge and accept Something Higher.