As this is a space for creatives, and I’m writing to a lot of creatives, I thought it would be fn to dedicate a few posts to the creative process. I will lean heavily on Iain McGilchrist’s The Matter With Things initially, as we layout a bit of a neurological perspective on creativity, and then, probably, onto other issues.

No doubt you have come across articles, courses, books, podcasts, etc, that are essentially promoting “The 12 Steps to Creativity”, or “How to be creative in 3 easy lessons”, or “The Complete Guide to Becoming a Creative Genius”. If it’s a course it’s probably on special right now; $1,325 worth of secret ingredients, but only $99 if you sign up in the next 3 minutes. But is creativity a thing that can be taught from a book or an online course? Is the budding horror author missing a channel that Stephen King somehow has tapped into? Did Liu Cixin follow an ancient formula allowing him to conceive and write the Three Body Problem trilogy?1 Did Tesla just have a brain wired in a weird way?

Creativity and the arts in general have been under pressure to be ‘equitable’ in this woke western world, and so everyone is touted to be especially creative - to discriminate between creativity and crap is ‘racist’, ‘bigoted’, ‘hater’, or some other equally meaningless slur. So, the following analysis of creativity, you might find, is at odds with so called ‘cultural norms’ of our times. Let this be a trigger warning: Creativity is not equally distributed. I imagine that once upon a time this was an obvious fact that was rarely articulated. But I remember growing up as a kid in the 70s and 80s where you were told you could ‘do anything’ – no creative endeavour was beyond you – this is what ‘good’ parent told their kids. And naturally kids believed their parents… until flung out into the realities of the world (and themselves) and it was obviously not so (bar a very few who’s touch turned all to gold, or so it seemed).

But what did that generation of parents know about the genesis of creativity as they pushed all their kids into the ‘gifted’ classes, offended at any suggestion their little geniuses were average across most spheres? Probably not a lot. Let’s have a look at the neurological perspective first.

Firstly, let’s establish that creativity is a difficult thing to see from brain studies. Yes, we can ask people to do problem solving pinned down in the claustrophobic cacophony of fMRI scanner. But what relation does this activity have to real-world creativity? Only a left-brained data collector, ignorant of any contextual influences, would imagine the unnatural environment of the fMRI scanner and a relaxing walk in the woods are the same thing when it comes to seeing what happens in the creative brain.

If I can just cut to the chase, I’d say there is no formula for creativity, it cannot be forced or procedurally enacted, nor is it totally random. The essence of creativity is an enigma. Some comfort for those who did pay the discounted $99 for the ‘three easy lessons on becoming a creative genius’, only to find out that procedures were antithetical to the creative process. Don’t worry, it wasn’t you, it was the company trying to sell you that brain exercise app.

Nevertheless, we desire to analyse creativity (as we desire to analyse everything these days) and there are some characteristics of the phenomenon we can glean from certain observations and measurements, but they are unlikely to tell the whole story. A story that, to the horror of the equity crowd, leaves some people out. Colin Martindale, a psychologist who used EEG to study creativity, said that

Creativity is a rare trait. This is presumably because it requires the simultaneous presence of a number of traits (eg, intelligence, perseverance, unconventionality, the ability to think in a particular manner). None of these traits is especially rare. What is quite uncommon is to find them all present in the same person.

Those who create truly new and innovative things are rare – I think we can agree with this. There is a degree of creativity, drawing together factors that we would not usually combine in order to solve a problem or come up with an alternative, that may be more common. I don’t want to argue that the majority of us are not creative, far from it, there’s absolutely a creative aspect to humanity, but at a higher level, as we will see in a moment, the creative process is somewhat out of our hands (‘hands’ being a metaphor for the deliberate manipulation of a thing for our use).

There are many ways to look at the process of creativity and one of those is simply to consider three stages: preparation, incubation and illumination.

1) Preparation is both conscious and unconscious – acquiring skills and knowledge in conjunction with mulling things over unconsciously – preparing the ground, if you will. Obviously there are many aspects of preparation that are within our capacity – to do a masters and then PhD in theoretical physics in preparation for that breakthrough equation you dream of. The formal and casual discussions with peers about the problem, the dreams.

2) The second stage of incubation is fully unconscious, and is actually impeded by conscious effort, and it is here that the seed of an idea is growing. This is the forgetting the whole thing and going for a walk, a swim, a sleep. It’s the sabbatical that gets you out of the university and its tedious intricacies so you can ‘clear your head’.

3) Thirdly there is the illumination phase, the unconscious flowering of the creative idea, without conscious effort, resulting in insight, that “light bulb” moment. It comes in a dream, on a walk, when watching an old film and that one line jumps out at you – ‘Eureka!’

Because the process is largely unconscious, we can’t make creativity happen. ‘Damn it Winston’, says the left hemisphere, ‘there has to be a method!’. But what we can do is attend in a way that doesn’t inhibit creativity from emerging. This attending is open, yet with some intimation of what is coming. You have some idea of what it might be like, but you can’t (and don’t want to) put your finger on it exactly. There is aspiration, trying, grasping, but then necessarily a relaxing, a stillness, and then the illumination. They ‘trying and grasping’ may also be the preparation, the searching out, the integrating of knowledge and experience, which is priming the pump but not the drawing of the water. The unconscious requires an openness to the unknown and undetermined, a release of control, and free associations, to allow it to be creative. None of which is particularly appreciated or even understood by the left hemisphere, but this is the realm of the right. The conscious mind would try to pin things down into something known, tangible, determined, and this inhibits the creative process. We will get to lesion studies a bit later which suggest it is parts of the left prefrontal cortex that actively inhibits such creative capacity. That very same area of the brain so functional for the practical scientist who desires processes to be explicit, neat, categorical, known.

We can also talk about the interactive cognitive requirements of the creative process, which are a number of co-occurring and interactive levels of consciousness. Broadly they are generative, permissive and translational requirements.

The generative requirements is that capacity

to think of many diverse ideas quickly, demanding breadth, flexibility and analogical thinking – seeing likeness within apparently dissimilarity. This could be, as often is, summed up as ‘divergent thinking’, a term that is deliberately (and appropriately enough) loose, but suggests the bringing together of non-adjacent ideas, adaptability of thinking and originality of approach. (McGilchrist, 2022, p. 242)

Convergent thinking (the antithesis to divergent thinking) is the ability to find the single ‘correct’ answer, a hallmark of most of our educational institutions I’d say. The ability to recall the ‘correct answer’ or to work it out from conventional logic, is at odds with the creative capacity to form novel solution or perspectives. Novelty that come out of perceiving connexions, shapes, relationships, Gestalten that have not been seen before.

Steve Jobs said of creativity,

Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things… A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.2

It's interesting that Steve emphasises diverse experience here as a key, and this is likely to be so, but may not be universal priori for creativity. My own experience is that depth of understanding and knowledge of a particular field juxtaposed with a common, everyday experience is fodder enough for a creative outcome. Actually, I’ve known people with very limited diversification of knowledge and experience but with great depth in their own field, who have demonstrated great creativity. As was said above – there is no formula.

From what we know of the hemispheres, all of the requirements for creativity reside in the right hemisphere – the breadth of vision, capacity to make distant links, flexibility, contextual awareness and tolerance for ambiguity and imprecision. The left hemisphere comes into play when a new idea needs to be refined, made practical, categorised, but not in the beginning. In fact, later we will look at what happens when the left prefrontal cortex is damaged and the capacity to transform a creative idea into a concrete reality is severely inhibited or made impossible. However, at the start, the activity of the left hemisphere would not be complementary when creativity is germinating.

Permissive requirements are about getting out of the way of the creative process. We may not be able to make creativity happen at the unconscious level, but we can certainly not do things that would inhibit creativity. Trying hard (or trying hard to not try hard or trying a systematic approach or random approach) or trying anything at all, is not helpful. Of course, the left hemisphere, needing clarity and control, is only going to get in the way of the right hemisphere which is open to intangible potential.

The unwillable nature of creativity depends on the fact that the important processes are going on unconsciously, and, as the process progresses, are, at the most, on the fringes of consciousness… It has similar characteristics, on a large scale, to the ‘tip of the tongue’ phenomenon, on a small scale. If I forget a name while I am talking to someone, I feel obliged out of courtesy to cut the matter short by giving them a clue – which is, however, often fatal. ‘Oh, you know, terribly famous German philosopher, name begins with a K – I’ll forget my own name next – come on, works are impenetrable – name begins with a K, I’m pretty sure’. ‘Kant?’ ‘No, no – oh well, forget it.’ A minute later: ‘Damn it, Heidegger, of course!’ The only useful thing to do is to relax and to avert the mind’s eye. Then it will come of it’s own accord. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 246)

How often have we been in this situation! Trying harder just makes the thing more elusive, until we turn our attention to something else, and then the thing pops up. The spotlight of the left hemisphere searches, with its narrow beam, tightly knit arras of neurones for what it already knows and thus hampers the open creativity of the right hemisphere. “Like the man who was found searching for his keys, not where he had dropped them, but under the lamplight, because that was where he had enough light to search.” (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 247)

The generative and permissive requirements operate together, but the third requirement, translation, can be postponed. This is about how to make something out of the insight and is an integral part of the creative process. It also requires an openness to possibilities and all the qualities of the right hemisphere. The execution of the translational process may well, and most likely, involve the skills of the left hemisphere, but it must not get involved too quickly. To be truly creative the rules and procedures so natural to the left hemisphere, need to be put on hold while connections and possibilities are freely explored by the right. Once the illumination has a direction to make something out of it, then the reasoning, calculating left hemisphere has something to work on. It is like bringing your drawings of a dream home to the architect with little regard for the practicalities of load-bearing beams, or the exact cladding to give that look. It is then the left hemisphere that is better equipped to break it all down into categories, formulas, processes and procedures to realise the dream.

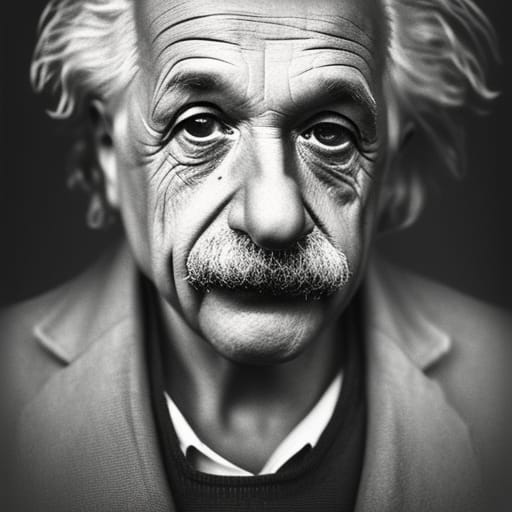

So from a brain perspective there is no localisable creativity ‘centre’, nor clear mechanisms and brain correlates that we can put our finger on and say ‘there’s creativity working in the brain!’. We can’t look at the brain of Einstein and say ‘Oh, there’s the creativity part!’.

This might be enough for now; I don’t want to get too long-winded. Let me know your thoughts in the comments and I’ll move onto more of the same in a future post.

Reference:

McGilchrist, I. (2021). The matter with things: Our brains, our delusions, and the unmaking of the world. London: Perspectiva Press

From the archive:

For those sci-fi fans who have not read Liu Cixin’s trilogy, you are missing out!

wired.com/1996/02/jobs-2/

I am making $3.15 an hour working from home. I never imagined that it was honest to goodness yet my closest companion is earning $39.55 a month by working on a laptop, that was truly astounding for me, she prescribed for me to attempt it simply. You too could be making this much from the comfort of your home, or while flying to London in your Learjet, or summering in the Caribbean. Boy am I gad I took notice of those spam comments on Substack! I would never have discovered the astounding financial opportunities I have without any effort, or even having to think much, or even write good. You too can learn the secrets of unlimited financial, social, political, and physical success just by clicking on the subscribe button above.

I'm volunteering (yes, working for free) for a project that I thought required, or at least would benefit from my creativity and especially my editorial skills (honed over the course of many years by working for free for my insufferably-bad-novelist father), and I was recently told that my creativity and editorial skills are superfluous and not appreciated. They want me to just copy and paste stuff into a spreadsheet. For some reason this reminds me of an old Yiddish joke: A poor Jewish man wants to enter the synagogue on Yom Kippur to pray, but he can't afford the ticket price. So he tells a white lie to the doorman: He needs to bring an urgent message to a cousin who's inside. The doorman relents, and says, "Okay. Go on inside. But don't let me catch you praying!"

I know. It's a bad analogy. It's close enough for a laugh, though, right? "Just don't use your editorial skills or your creativity on this project, whatever you do."