As I journey through the incredible work by Iain McGilchrist: The Matter With Things, I thought I’d summarise Chapter 9 “what schizophrenia and autism can tell us” for our mutual benefit. The two volume set by McGilchrist is not a light read, nor is it cheap, and I don’t suspect the casual reader will be picking up a copy. So summaries may serve us well in this case.

In this chapter McGilchrist takes us into the minds of schizophrenics (and autistics) who experience the world with a hemispheric bias toward the left - a bias I’ve written much about on this Substack. By getting into the heads of those who experience the world in this way, we may better see and understand similar tendencies in the culture at large – as we have similar imbalances in our sociocultural attention and perceptions of ourselves and the world. If we accept that our awareness shapes our perception of reality, then imbalances in the larger population will impact the social perception of the world. We should be aware of any population wide hemispheric imbalance and take action, lest our world becomes increasingly lopsided (if it hasn’t already become increasingly left-hemisphere dominant).

Diseases of the brain and mind, though disruptive and distressing for the individuals who have to suffer them, offer us rare insights into human experience as a whole, for which we should be grateful. They throw into relief our normal reality by showing us how it could be altered and appear quite differently to us. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 306)

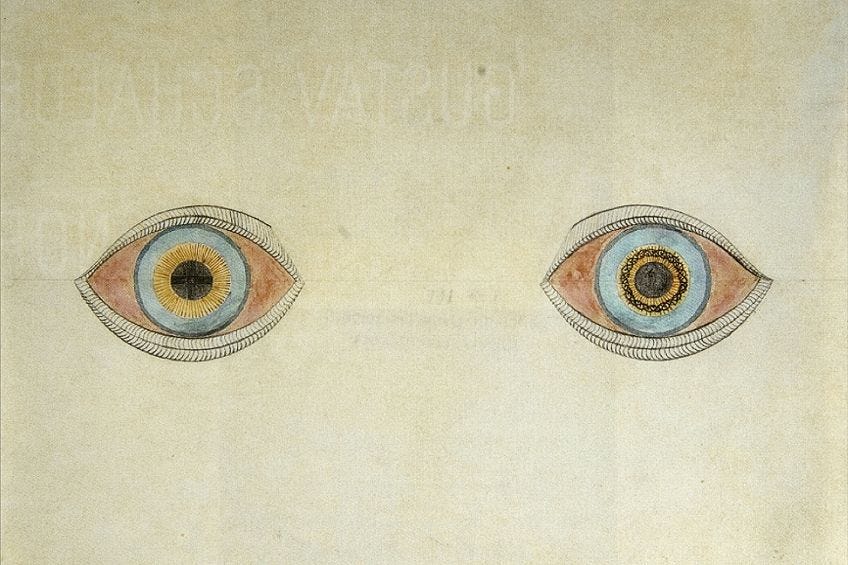

Schizophrenia and autism are, clearly, distinct conditions, however they do have many similar features that are characteristic of right hemisphere deficits. These conditions prove interesting when trying to understand the world from the perspective of a dominant left hemisphere. That is not to say there are no deficits on the left hemisphere, as there are disturbances of language in both conditions, but it is in the perception of reality from the left hemisphere that seems prominent in both schizophrenia and autism.

Again, we are interested in how this perception is broadly manifest in our modern culture. It is the subject’s experience of being in the world, how the world is for them in a very authentic way, that we must appreciate and not think of the subject as simply suffering pathological distortions of reality. The schizophrenic is not conscious that they are suffering from a “pathological distortion of reality”. They are simply conscious of their perception of reality. When we start to see through their eyes and then look around at the rest of the world, we are able to discern some similarities. Indeed, McGilchrist contends that three important functions that are dependent on the right hemisphere – sustained attention, reading faces, and empathy – are not only impaired in schizophrenia and autism, but also seems to be increasingly impaired in the younger ‘normal’ population today. Is it possible that we are living in a world that is increasingly reliant on the left hemisphere, which caters to the left hemisphere, and is, therefore, developing a continual feedback loop that takes us further into the world of the left hemisphere? The Distinguished Professor of Psychology, Louis Sass, certainly thinks the core of modernism closely resembles the experience of schizophrenics in his book Madness and Modernism: Insanity in the Light of Modern Art, Literature and Thought. (which I will dive into at a later date - another challenging read like McGilchrist, but rich in understanding the madness of our age through the madness of schizophrenia).

What is the phenomenology of the right hemisphere and that of schizophrenia?

We have seen that every kind of visual distortion and hallucination found in schizophrenia is also found in right hemisphere dysfunction, along with auditory, tactile and olfactory hallucinations. As far as delusions go, not merely paranoia, but monothematic delusions such as Capgras1 and Cotard2 syndromes are found not just in right hemisphere disease but in schizophrenia. Schizophrenic patients are sometimes hard to tell from right brain-damaged subjects. (McGilchrist, 2021, pp. 308-309)

When it comes to affect, there tends to be an emotional indifference and passivity in both schizophrenics and right hemisphere deficits. This is manifest in a multitude of deficits involving the ability to feel and express emotion as well as to perceive and understand the emotional signals of others (similar observations can be made in relation to autism). In fact, there are many aspects of the implicit (those things that are not literal, such as irony, sarcasm, and humour) that are lost to the schizophrenic and the left hemisphere, with a propensity to miss the larger context of a social interaction, a story, or a conversation. There is an over reliance on the explicit and literal which can be rather barren of the richness and subtleties in our normal experience of the world. Theory of mind – the capacity to understand another’s point of view – is also problematic for the left hemisphere, the schizophrenic and the autistic, as they always come back to a self-referential perspective from what they already know and find it difficult to imagine being “in another person’s shoes”.

I think, as far as our current culture goes, we could see an “emotional indifference” at play, especially from those in places of power. An over reliance on the explicit and the literal also seems to be evident in our current age.

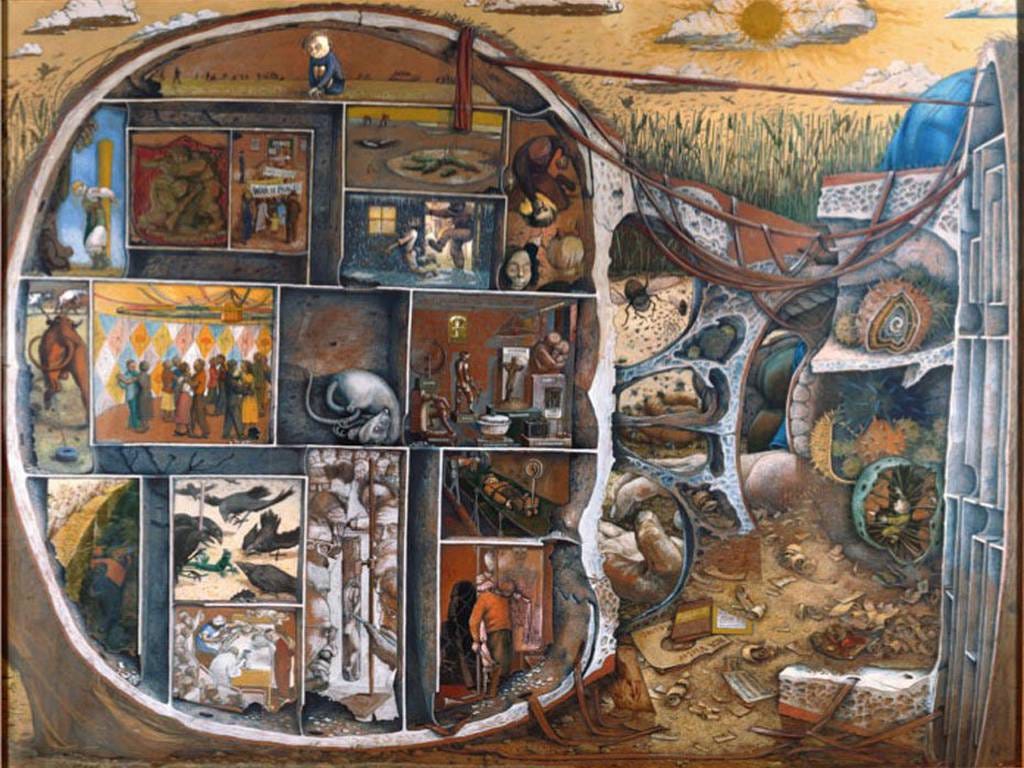

Schizophrenics also have difficulty in seeing the whole – there is a breakdown in the capacity for Gestalt perception, as is the case with the left hemisphere.

Schizophrenic subjects have a reduced capacity to see the whole pattern; they respond faster to local targets; and tend to adopt a ‘piecemeal’ approach in the description of complex images. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 311)

The problem with not seeing the whole is that you miss the context and see a collection of things as individual and decontextualised that may not hold a lot of meaning.

Once again, I see this happening today - missing the larger context - in health, politics, the noise on social media, etc. So much is decontextualised, packaged and consumed as little ‘bits’ of ‘truth’ or ‘knowledge’ or ‘information’, while we miss the broader picture.

Meaning is more often than not based in contextual relationships. There is also a sense, with right hemisphere damage and schizophrenia, that situations are not real, people are play-acting, and there is an absence of “common sense”.

There is a loss of the stabilising, coherence-giving, framework-building role that the right hemisphere fulfils in normal individuals. Both exhibit a reduction in pre-attentive processing and an increase in narrowly focussed attention, which is particularistic, over-intellectualising and inappropriately deliberate in approach. Both rely on piece-meal decontextualised analysis, rather than on an intuitive, spontaneous or global mode of apprehension. Both tend to schematise – for example, to scrutinise the behaviour of others, rather as a visitor from another culture might, to discover the ‘rules’ which explain their behaviour. The living become machine-like: as if to confirm the primacy of the left hemisphere’s view of the world, on schizophrenic patient described by Sass reported that ‘the world consists of tools, and … everything that we glance at has some utilization. (McGilchrist, 2009, p. 392)

Other aspects of schizophrenia and right hemisphere damage include habits of jumping to conclusions, stickiness of gaze and fixation on things, and a technical, non-living perception of anything in the right field of attention and denial of things on the left.

In our current political climate ‘jumping to conclusions’ and ‘fixation on things’ is the norm, especially from a technical perspective. The perspective of the right hemisphere that deals with a bigger, more complex ‘whole’, and can handle ambiguity and contradiction, is largely ignored.

There is a lot to these peculiarities, but the big picture is that under-functioning of the right hemisphere and over-functioning of the left in schizophrenia emulates the experience of right hemisphere damaged patients.

To drive the point home McGilchrist goes on to describe the brain correlates of schizophrenia and right hemisphere deficits (which are substantial), and then the phenomenology and brain correlates between autism and right hemisphere deficits (also substantial), before diving into the experiential world of the schizophrenic – which we will briefly summarise below.

The World of the Schizophrenic

The Franco-Polish psychiatrist Eugéne Minkowski gives us an interesting list of antithetical pairings of hypertrophied (exaggerated) aspects of intellect and atrophied (diminished) aspects of intuition (which we could also correlate with exaggerated left hemisphere and diminished right hemisphere function) in schizophrenia:

Atrophied/Hypertrophied

Life/Map

Instinct/Brain

Feeling/Thought

‘faculty of penetration which synthesises’/‘analysis of infinite details’

Trust in impressions/Demand for proof

Movement/Immobility

Events and persons/Objects

Presence/Representations

Goal/Preliminaries

Time/Space

Flow/Measure

These characteristics not only correlate with right hemisphere damage and an over-reliance on the left hemisphere, but they are also characteristic of the way we live life today. The mechanical bureaucratic life of the exaggerated left hemisphere (and subsequent lack of the living embodied vitality of the right hemisphere) can be seen all around us - and so obviously in the bureaucratic handling of the so called pandemic.

The fragmented attention of the schizophrenic (and the autistic) leads them to a conscious awareness of massive amounts of data but with little discrimination as to what’s most important in any given circumstance.

Think of all the systems we have in place to accumulate massive amounts of data all the time on everything!

The autistic person can become overwhelmed by the amount of information and detail that comes at them without any real hierarchy of attention (i.e. every bit of detail seems as important as every other bit) – everything demands attention. Consider this report from a schizophrenic patient:

Everything seems to grip my attention although I’m not particularly interested in anything. I am speaking to you just now, but I can hear noises going on next door and in the corridor. I find it difficult to shut them out and it makes it more difficult for me to concentrate on what I’m saying to you. Often the silliest little things that are going on seem to interest me. That’s not even true; they don’t interest me, but I find myself attending to them and wasting a lot of time this way. I know that sounds like laziness, but it’s not really. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 330)

I know in my own work that this environment of too much information coming at me, vying for my attention, without any sense of hierarchy of importance, is both stressful and energy consuming. I am self-aware enough to know I play the major role in allowing this data flood to continually engage my curiosity and need to know more data points. So, it’s not as if I’m just a passive victim of the ‘system’, but rather my left hemisphere dives headlong into the fray – for that is what the system caters to so very well.

When we are out of touch with sensing the whole, the living flow of time, the seamlessness of it, the embodied intuition of existence, then things become increasingly abstract and static. We only see bits in a static sense – we don’t see the overall direction, purpose or meaning. To make sense of the world we have to put all the bits together to see the whole rather than seeing the whole before deconstructing it into bits. Again, here are some observations from patients:

It’s like eating a soup where you taste the individual ingredients: you taste the flavour of the soup itself only after reconstructing it.

I have to put things together in my head. If I look at my watch I see the watch, watchstrap, face, hands and so on, then I have to put them together to get it into one piece.

Such fragmentation of perception has a far-reaching impact where one can feel alienated from the body and a complete loss of self. I think we can see this on a social scale - talk to enough young people and you will get a sense of just how many have a sense of fragmentation and loss of self, they are overwhelmed and don’t know who they are or how they fit in.

Alienation from the body

Fragmentation leads the schizophrenic into a state of extreme disembodiment or a sense of radical separation from themselves. They can feel distant from themselves, or that their body is not theirs, they live in a third person without a vital link to their own body. Not only is there a sense of disembodiment but that the body itself can seem hollow or just a frame. Furthermore, this fragmented perspective drives an atomistic, abstract view of the world and a compulsion to analysis – “patients with schizophrenia become excessively analytic in their approach to life” (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 333)

Loss of Self

If you are disembodied and your body seem alien to you, or you feel that you are not you but in fact someone else, it goes without saying that identity is problematic. The loss of self is a result of alienation from the body, and without a self, there is no capacity for intersubjectivity. There is a breakdown of betweenness, between self and other, an awareness necessary for realising and negotiating relationships.

McGilchrist draws a parallel here between this aspect of schizophrenic pathology and the alienation we can feel in the world and with others. There is a rise in the dissociative disorders in which a sense of identity is diminished or lost, and on a broader scale a sense of the individual as not having a place in the community, being lost in the global bureaucracy – their identity being swallowed up, if you will. The sense of self that comes from being in a shared context of community can easily be eroded in the modern world. As I mentioned above, this is a big problem today, especially among young adults (in my experience) who find identity elusive and negotiating relationships difficult (not the difficult that all young people have experienced since the dawn of time in finding meaningful relationships, this is a few notches of difficulty above that).

When there is no self, there can be no other; and when there is no other, there can be no self. What in the past gave us that stable ‘other’ was our culture, stretching in time back in the past and forwards into the future as part of a living tradition; ramifying laterally into kin and community, and the land out of which we came and in which we live. But once ‘anything goes’, nothing goes. There is no purchase between the individual and the world. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 335)

Devitalisation

McGilchrist points us to a quote by a schizophrenic patient, that describes the perspective of the left hemisphere and more broadly the plight of the modern world – a fragmented, disembodied re-presentation of static things in a lifeless, emotionless existence. For the schizophrenic this equates to a feeling of devitalisation. It’s worth repeating here (italics indicate hemispheric implications) …

Everything around me is immobile. Things present themselves in isolation, each on its own, without evoking any response in me. Certain things which should produce a memory, evoke a host of thoughts, present a picture, instead remain isolated. They are understood rather than experienced. It is as if a pantomime is being played out around me, one in which I cannot take part – I remain on the outside of it. My critical faculty remains, but I lack any instinctive feel for life. I can no longer shift between major and minor key, and yet no life is supposed to be spent in a single tonality. I’ve lost contact with all sorts of things. Any notion of the value and complexity of things has disappeared. There’s no flow between me and the world: I can’t abandon myself to it. All around me is completely and utterly fixed. I have even less room to manoeuvre with respect to the future than I have with the present or past. There is, inside me, a sort of routine which makes me quite incapable of imagining the future. The creative power is abolished in me. I see the future as a repetition of the past. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 336)

This unreal repetitive existence devoid of life and creativity, restrictive and emotionless, is the life lived without the right hemisphere. Everything is objectified, including ourselves. Everything is an abstract and mechanical thing. Classes and categories replace the real living interconnected world or relationships.

This is the bureaucratic perspective: abstract, grossly simplified, dealing in categories, reducing life to puppetry. And it is often expressed using nouns in preference to verbs, and abstract nouns in preference to concrete ones. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 338)

I remember years ago there was a chap who would pop up now and then on a forum I used to run. At first glance you could mistake his long monologues as some sort of insightful philosopher with more depth of understanding about high and lofty things than most of us could fathom. But on a second glance you realise that everything is a completely abstract, disconnected, adjective excessive description of nothing in particular and made no sense whatsoever. It soon became apparent that this chap was schizophrenic and after a number of frustrating attempts at a reasonable conversation he did establish the fact that he was schizophrenic. I could not, however, ascertain if he was under the care of a mental health professional as his philosophically sounding, but ultimately empty, monologues flew off into every direction except his lived relationship with a psychologist or psychiatrist.

What was apparent for this chap was that abstraction, the words and categories, were more real to him than whatever they represented. Probably not that different to contemporary political and scientific narratives where statistics and categories become more important than the lived reality and relationships in the real world.

Mechanistic World

For the schizophrenic and the left hemisphere, everything is mechanical, including themselves. I’ve touched on this many times in the past and is a remarkable element of schizophrenia, left hemisphere dominance, and modernism. Processes are seen as mechanical, like sex being a mathematical algorithm, the soul a chemical reaction, perception as being a camera, memory a fax machine, etc. McGilchrist asserts that schizophrenics will often describe themselves as machines or computers and are controlled by machines. But this perception is not far from a modernist one in which the human being is reduced to a mechanism, and an algorithm, and eventually we will be able to understand all the mechanical parts and thus understand ourselves.

What comes to mind in this regard of a mechanical view of things organic and living, is the move toward human augmentation through technology and the whole “4th Industrial Revolution” push by the likes of Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum. A recent publication by the British Ministry of Defence “Human Augmentation – The Dawn of a New Paradigm”, speaks about people as technology platforms, integrated and interchangeable with the machine world:

Human augmentation will become increasingly relevant, partly because it can directly enhance human capability and behaviour and partly because it is the binding agent between people and machines. Future wars will be won, not by those with the most advanced technology, but by those who can most effectively integrate the unique capabilities of both people and machines… Thinking of the person as a platform and understanding our people at an individual level is fundamental to successful human augmentation. (p.11)

This augmentation of the human ‘platform’ involves genetic germ line modification, genetic somatic modification, invasive and non-invasive brain interfaces, exoskeletons, pharmaceuticals and other nanotechnologies. The computer-brain interface being proposed by Elon Musk is a classic example - just joining one type of machine to another.

McGilchrist suggests that most scientists and academics are so thoroughly schooled in this mechanistic view of the living world that they cannot see that there is a problem, let alone escape it. It is celebrated, as in the paper above, as a welcome paradigm shift toward a better world where the human ‘platform’ has much more utility than it currently offers. Here we have the left hemisphere bias toward utility and machines – just as in the world of the schizophrenic where the organic is machinery, and a sense of self is lost. I’m certain the technocrats who rule the world see humanity as a platform for utility.

In fact with this sort of thinking there can be an aversion from anything natural and spontaneous. This includes the natural world, and withdrawal to, and even obsession for, that which is man-made, that which has utility. If there is any attention toward the natural world, that seemingly has no utility, is to make it useful. Again, we can draw similarities between the schizophrenic mind and the bureaucratic attitude toward nature and the questions are around it’s utility: “how is it useful?” And although not openly phrased this way, “how is it to be exploited?”

[What comes to mind here is the shelving of untold numbers of patents and inventions of alternative power sources and innovations by Big Oil and other corporate heavyweights - the attention to the natural world in this case is only about exploitation by those with the money and the power.]

Hyper-rationalism

The schizophrenic mind, as with the left hemisphere, lacks an intuitive sense of the whole and of the natural flow of time. Things are stilted, static, in pieces and must be re-assembled in a logical fashion to see what it is and how it works in a mechanistic way. The autistic brain as well, can be excessively systemising with rigid rules and procedures as opposed to intuitive intersubjective flow of things. In other words, things only make sense in terms of logic, structure, pieces fitting together for utility.

Ludwig Binswanger reports the case of a father who placed a coffin under the Christmas tree for his daughter, who was dying of cancer, because the coffin was, he correctly reasoned, something she was going to find useful – thus a very suitable present. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 351)

[Interestingly the linear/logical cause/effect way of thinking in terms of discrete ‘parts’ of a mechanism bound by rigid rules is reinforced by our education, Western languages, and philosophy - whereas in some other cultures and languages (I’m thinking in particular of Hebrew, Chinese, and Japanese), there is a non-linear, circular, and more ‘complex-system’ way of thinking and reasoning about things.]

Narrative that necessarily incorporates the flow of life is difficult for the left hemisphere to understand. It is, at best, used to link things together but the interpretive skills needed to understand a narrated story is often lacking. Schizophrenic subjects, and often autistic ones, often gravitate to mathematics, physics, or some other area that rests on logical linear constructions. Swiss psychiatrist Roland Kuhn reports on the case of Franz Weber, a schizophrenic, who was on a mission to collect and store all human knowledge in a static and abstract way. All the implicit, fluid activity of life, was to be recorded as static structural, procedural detail. He wasn’t concerned about the actual content, but that there should be tables and figures that he would specify. Procedure was more important than meaning – something that is not unfamiliar in today’s bureaucratic world of academia! I would also point out that ‘procedure being more important than meaning’ has been well demonstrated by health officials during Covid in the most startling and bewildering display of bureaucratic insanity.

Another schizophrenic patient attempted to understand how to interact socially by scrutinising the details of other people’s behaviour, as if he were some kind of technical observer, perhaps an anthropologist; he wanted to encode the steps involved in making friends and to devise ‘new schemata’ for relationships on his hospital ward. Other subjects speak of understanding from the outside like a scientist, attempting to make sense of others’ mental states through observing everyday ‘transactions’, or ‘scientific’ analysis of the workings of ‘intelligent mechanisms’ (‘I study people. I want to understand how they are inside… I studied a system to intervene at the right moment in conversations’). (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 352)

The problem here is a hyper-logic that overrides common sense elements evident to most of us, and this lack is often noticed by the schizophrenic but they are at a loss as to define what exactly is lacking. The most delusional subjects can be the most logical, jump to conclusions the fastest, and are the most intolerant of ambiguity and uncertainty. For the schizophrenic a plan is all important. The symmetry, regularity, certainty, theory, are the assuring factors, not life itself but the algorithm that describes it – much like some scientists, analytic philosophers, and bureaucrats! The right hemisphere, however, brings a sense of grounding amid ambiguity, and essential skill in a world where nothing seems certain.

Literalism

“When you doubt everything, all meaning that is not literal and unambiguous becomes a threat: how to make sense of it?” (McGilchrist, 2021, p.354)

Literal-mindedness, from a lack of grasping metaphor and a pronounced reification (objectification or ‘thingification’ – in Marxist theory this idea is partly the “transformation of human beings into thing‑like beings which do not behave in a human way but according to the laws of the thing‑world“ (Petrović, 1965) ), is typical in schizophrenia, autism and left hemisphere dominance. In the case of psychopathology, the literal-minded patient will do all manner of explicit and literal things to make sense of the world. One patient, for example, presented a wine-stopper to her analyst, believing him to be an alcoholic like her father, so he could ‘stop’ drinking wine.

Hyper-consciousness

To engage in the spontaneous, the implicit, such as embodied wisdom and intuitive wisdom, there are certain things that must remain in the background. The trouble with the left hemisphere is that it keeps things in the foreground that inhibit our capacity to tap into the implicit. So, for schizophrenia patients the spontaneous becomes a conscious effort…

None of my movements come automatically to me now. I’ve been thinking too much about them, even walking properly, talking properly and smoking – doing anything. Before they would be able to come automatically…

I am not sure of my own movements any more. It’s very hard to describe this but at times I’m not sure about even simple actions like sitting down. It’s not so much thinking out what to do, it’s the doing of it that stick me… (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 355)

The simple action of sitting down, the mechanics of it, the motor movements, should be implicit, they should be in the background of awareness, not in the foreground as with the patient above. This condition also halts the sense of flow, things are stilted, everything needs to be planed and consciously executed. In the realm of relationship there is also a lack of the implicit. Rapport and emotional connectivity is replaced with a forced, intellectualised, calculated response to another, rather than any sort of spontaneous connection. How relatable is this to our relationship with government! If you feel your relationship with government is ‘forced, intellectualised, and calculated’ then I’d say we are dealing with a schizo entity.

Re-presentation

In schizophrenia the experience of time breaks down and there is a resulting lack of flow and continuity in the experience of life. With this lack of flow there comes a re-presentation of the world in such a way that nothing seems substantial, or indeed real. It is as if everything is a performance, a façade, an impression of being real but ultimately unreal. People are not really going about life as they seem but are just play acting, going through the motions, it’s as if it is all a big performance – it’s The Truman Show, and the schizophrenic subject is Truman. Not unlike our modern perception of the world through screens, where images come at us via flashing, coloured pixels at various frame rates, building an illusion of life, the truth and reality of which is becoming increasingly suspect.

Engagement with real persons is replaced by a utopian interest in abstract humanitarian values: ‘I love Mankind, but I detest humans’.

According to a patient of Minkowaska’s:

I have managed to detach myself from the realm of the material, and in my actions, I am guided by impersonal principles. I respond not to a limited environment, but to the whole world. I’ve come to live for the idea and look on people impersonally. I’ve been united in thought, not with human beings, but with humanity, and sought as far as possible to attain the absolute. I’ve submerged my filial love in a greater love. (McGilchrist, 2021, pp. 357-8)

For the schizophrenic everything seems to be a re-presentation of something, even if that something has just happened. There is nothing new and fresh. Everything is a repetition. This is the mode of the left hemisphere, to constantly re-present everything, a constant reconstruction of things to keep the world in awareness lest it disappears. The recording of things becomes important, as the record – the photo, the written account – provides the substance and assurance of the world out there. Systematic and meticulous record keeping is also the hallmark of bureaucracy that can lose a human connection, such as was expressed in the incredibly detailed and meticulous record keeping by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

I wonder if the digital ID for everyone on the planet is also a reflection of this attribute of re-presenting everything as a record, an abstraction, something more easily manipulated than a real personality.

McGilchrist points out the modern saying about keeping accurate records, “if it’s not recorded, it didn’t happen,” and the fact that in some contexts the representation is more real than what happened! We are in an age obsessed with keeping records, both in work settings and in our private lives. Think about the ‘selfie’, taking photos of our meals when dining out and relentless updates on social media. In many of these cases it seems the representation is more important than the actual thing and at times the representation, a photo touched up by this app or that, doesn’t even accurately represent the real thing but becomes the object of greater reality in a Facebook or Instagram feed.

A Spanish professor of animal physiology became obsessed with keeping records of everything he did so he would have something to show when he looked back on his life. He wrote down everything he did, ate, saw, and then started to take photographs, every 30 seconds, amassing more than a million of them. So consuming was this attempt at recording his life that he had nothing to show for his existence except that everything was recorded.

I’m reminded of the scene in the movie The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, where the photographer Sean O’Connell (played by Sean Penn) does the antithesis of the record-keeping obsessed left hemisphere. He is in the Himalayan mountains to take photos of a rare snow leopard. When the snow leopard eventually shows itself, Sean doesn’t take the photo, he just observes. Walter asks when he’s going to take the photo, to which Sean replies, “Sometimes I don't. If I like a moment, for me, personally, I don't like to have the distraction of the camera. I just want to stay in it.”

Freezing time kills. Our age is one of re-presentation: photography, sound recording and film have become so important to us that they can come almost to supersede direct experience. We talk about an aide-memoire, as though we were preserving a memory. But research shows that photographs actually erode memories. The effect of taking photos is that they substitute for memories, as you can verify by thinking back to any travels you made some years ago of which you still have photographs: the photos tend to crowd out memory of all else. And time is sliced. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 364)

Nothing Flows

In a similar vein to “If it’s not recorded, it didn’t happen,” both the autistic and schizophrenic mind can feel that “if it cannot be measured, it doesn’t exist”. There can be a need to anchor reality by measuring. The frame-freezing mentality of the left hemisphere replaces whatever flows into maths – frame by frame and step by step. Which is why those on the schizoid-autistic spectrum can have great difficulty with narrative, which is essentially a continuity of living/ flowing expression, as opposed to a static representation like an equation.

Such a disconnection from the fluid world sees the schizophrenic trapped in a hall of mirrors, as it were, where symbols refer to other symbols - the abstract describes more abstraction. This departure from reality can end in a paradoxical life of feeling omnipotent yet impotent, grandiose yet insignificant. Just as it is with the left hemisphere, there is seemingly no in-between. Everything is either/or, black/white, there is no maybe, opposites cannot coexist and gradients disappear. There are only the extremes in what one sees, knows and believes.

…the schizophrenic subject appears to occupy extremes simultaneously: both sceptical to the point of paralysis about matters that must be taken for granted if one is to function at all, and yet gullible enough to espouse enormously improbable belief systems that are clearly delusional. Once the theoretical mind is untethered from the body and community, in which it is grounded, and from which it receives its intuitions, there simply is no longer any solid basis for discriminating truth from untruth. And once again one sees parallels in some kinds of belief systems driven by the irrationality of identity politics, which lead subjects to doubt everything except the validity of a bizarre conclusion which they feel driven to accept by formal rules. But never doubting the rules. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 369)

McGilchrist does not suggest that schizophrenia (or autism) is primarily a left hemisphere dominant condition, but rather phenomenologically these conditions are very closely related to the way the left hemisphere sees the world. Left to itself the left hemisphere, with its self-referential, internally validating, self-confirmatory perspective is not at all competent to make sense of the world. And worryingly the left hemisphere is extremely self-confident that it is correct and is more than willing to ‘go it alone’ and leave the right hemisphere behind if it could.

So, what can we make of the phenomenology of the left hemisphere? How do we see it from our virtual worlds of machines and screens? What of our culture, the administration of things, art, literature, film, medicine? I think we can see the bias toward the left hemisphere which makes McGilchrist’s work so fascinating and, I believe, so important.

When you are out of touch with reality you will easily embrace a delusion, and equally put in doubt the most basic elements of existence. If this reminds you of the mindset of the present-day materialistic science and philosophy establishments, as well as of the loudest voices in the socio-political debate, we should not be particularly surprised, since they show all the signs of attending with the left hemisphere alone. I live in the hope that that may soon change: for without a change we are lost. (McGilchrist, 2021, p. 375)

McGilchrist, I. (2021). The matter with things: Our brains, our delusions and the unmaking of the world. Volume one, the ways to truth. Perspectiva Press.

Petrović, Gajo. 2005 [1965]. "Reification." Marxists Internet Archive, transcribed by R. Dumain. Originally in T. Bottomore, L. Harris, V. G. Kiernan, and R. Miliband (eds.). 1983. A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Pp. 411–3.

UK Ministry of Defence, 2021. Human Augmentation – The Dawn of a New Paradigm. DCDC, Ministry of Defence Shrivenham, Swindon, Wiltshire.

Capgras syndrome (CS), or delusion of doubles, is a delusional misidentification syndrome. It is a syndrome characterized by a false belief that an identical duplicate has replaced someone significant to the patient. In CS, the imposter can also replace an inanimate object or an animal.

Cotard's syndrome is a rare disorder in which nihilistic delusions concerning one's own body are the central feature.

Excellent work. There is a lot to ponder here. We learn about what the right hemishphere does when we examine people who have some form of right brain injury. This "subtractive" examination is not uncommon. Here it is interesting. We cannot do a description justice by employing only left hemisphere techniques, so we look at the whole of the person, and then the absence of a component of the right hemisphere to understand the thing.

Meanwhile civilization rushes toward "optimization" in a transhumanistic frenzy led by people who have various forms of right hemisphere disfunction.

*edited to correct typo.