This post continues the exploration of the mind of man in this modern age in an attempt to understand how we have arrived where we have. Think of these posts as pieces of a very large puzzle1. If you missed the proceeding post that gives a primer for the natures of the left and right hemispheres of the brain you can find it here: The Divided Brain. Most of this material comes from Iain McGilchrist - an intellect I could not hope to match, but am honoured to be able to mingle his revelations with a few of my more meagre thoughts.

Modernity

Modernity was marked by a process of social disintegration which clearly derived from the effects of the Industrial Revolution, but which could also be seen to have its roots in Comte’s vision of society as an aggregation of essentially atomistic individuals. The drift from rural to urban life, again both a consequence of the realities of industrial expansion and of the Enlightenment quest for an ideal society untrammelled by the fetters of the past, led to a breakdown of familiar social orders, and the loss of a sense of belonging, with far-reaching effects on the life of the mind. The advances of scientific materialism, on the one hand, and of bureaucracy on the other, helped to produce what Weber called the disenchanted world. Capitalism and consumerism, ways of conceiving human relationships based on little more than utility, greed, and competition, came to supplant those based on felt connection and cultural continuity. The state, the representative of the organising, categorising and subjugating forces of systemic conformity, was beginning to show itself to be an overweening presence even in democracies. And there were worrying signs that the combination of an adulation of power and material force with the desire, and power (through technological advance) to subjugate, would lead to the abandonment of any form of democracy, and the rise of totalitarianism. (McGilchrist, 2009, pp. 389-390)

When I read this excerpt from McGilchrist I feel a sense of sadness over what was lost. Yes the industrial revolution and technology has brought much good to the world, but at a cost, it seems, of a social disintegration. Utility became the all-important value to which everything is measured and the wonder and value of the individual apart from utility became foreign.

Our identity and individuality in a sense have been diminished in the wake of industrialised capitalism and the requisite globalism. We are transient, without a solid sense of context, place, meaning, where nothing is absolute, nothing is certain. Expert systems, automation, symbols and avatars replace real experiences and the media fill our minds with a virtual reality full of abstractions and illusions.

Because we are social beings we have a deep-seated need for social attachments and those attachments contextualised in a place - a ‘home’, a place of ‘belonging’. Modernity, however, with its defining features of mobility, consumption, urbanisation, brings about a fragmentation of these important social bonds and the feeling that we don’t particularly belong anywhere. The lack of the sense of place threatens our identity and sense of community. Something I feel we are now so removed from that we can’t feel the loss, except maybe via a well crafted film set in times past when lives were grounded in family, place, community, and culture.

But this loss is not felt by the left hemisphere of the brain, the side, if you recall the last post that introduced the differences between the hemispheres, that is not concerned with such connectivity of family, place, community or culture. The left hemisphere doesn’t understand context, everything is decontextualised and perceived in isolation. A “family” is simply the addition of isolated individuals that grouped together form something that fits into a certain category - that of “family”. Relational bonds and all the richness of exchange, history, loyalties within emotionally attuned family members is invisible to the left hemisphere - it is rather more like a deck of playing cards where the only difference between an individual card and the deck is a matter of physical proximity. A sense of uniqueness is gone. And probably more important is the left hemispheres inability to grasp the whole picture, the framework, if you like, of the situation at hand which is necessary for what we would call common sense. The right hemisphere gives this appreciation of the whole and all the relationships that make up the whole, but the left is decidedly blind to this. The left hemisphere on its own is devoid of common sense.

The argument we will pursue here is that the modern and postmodern world is a world biased toward the perceptions of the left hemisphere. A situation that reinforces itself as the left hemisphere continually constructs a world around itself to reflect it’s own perception of reality - an echo chamber, if you like.

In the world of the left hemisphere everything is mechanical with some sort of utility or lack thereof. Everything is broken down into something that can be categorised and hopefully utilised in some way. This is fantastic for creating machines and manipulating things for utilities sake, but not much good for grasping the “big picture”, for intuition, and especially understanding relationships.

How This Reflects in Art

Louis Sass, in his book Madness and Modernism: Insanity In The Light Of Modern Art, Literature, And Thought, draws parallels between the experiences of the schizophrenic2 and the perception of the world in the modern and postmodern age.

What Sass picks up in modern culture and identifies with schizophrenia may in fact be the over-reliance on the left hemisphere in the West, which I believe has accelerated in the last hundred years. (McGilchrist, 2009, p. 394)

The schizophrenic has difficulty relating self to the world - Sass calls this hyperconsciousness. Elements of self that are usually unconscious and intuitive comes into awareness and every action (usually done unconsciously, like sitting down, walking, etc) takes up the conscious consideration. This awareness of automatic processes brings a certain detached and alienating attention. There is a focus on the body, its parts, the self (which has to be constructed from the products of ones observation of self), with a loss of the feeling of immediacy and intimacy with self - the self seems alien. The world and people become just objects with a lack of overarching context. There is a withdrawal from the external world and a turning inward to a world of fantasy.

Sass identifies the same phenomena that characterise schizophrenia in the culture at large. ‘I used to cope with all this internally, but my intellectual parts became the whole of me,’ says one patient. Compare Kafka, who speaks for the alienated modern consciousness, noting in his diary how introspection ‘will suffer no idea to sink tranquilly to rest but must pursue each one into consciousness, only itself to become an idea, in turn to be pursued by renewed introspection.’ The process results in a hall of mirrors effect in which the effort at introspection becomes itself objectified. All spontaneity is lost. Disorganisation and fragmentation follow as excessive self-awareness disrupts the coherence of experience. The self-conscious and self-reflexive ponderings of modern intellectual life induce a widely recognisable state of alienated inertia. What is called reality becomes alien and frightening. (McGilchrist, 2009, p. 396)

Nobel prize winner Dr Eric Kandel writes about art from the perspective of a neuroscientist and describes the development of 20th Century art as experiments in perception. For example Kandel writes that…

“Cézanne stopped trying to portray perspective realistically. Instead, he experimented with reducing the spatial depth in his paintings, as in the mountain landscapes of Montagne Sainte-Victoire, near his house in Provence. As the art historian Fritz Novotny has put it: “Within Cézanne’s paintings… the life of perspective has faded away. Perspective in the old sense is dead.” Moreover, Cézanne believed that all natural forms could be reduced to three figural primitives - the cube, the cone, and the sphere. (Kandel, 2012, pp. 215-216)

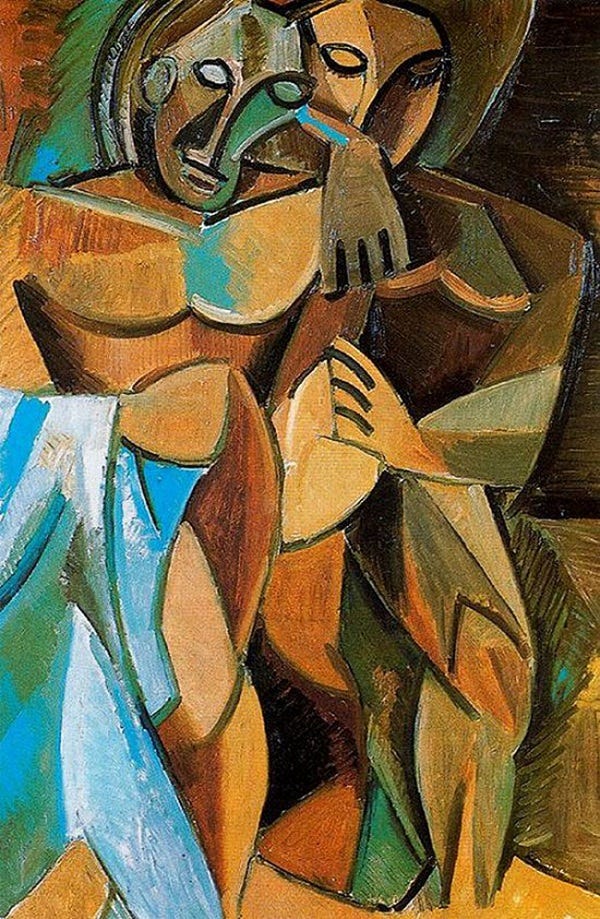

This led to the development of Cubism by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque - deconstructing and abstracting the essence of people, places and nature to simple shapes. Others3 continued the abstraction of things that seem to be a reflection of the left hemispheres take on reality. Kandel doesn’t draw this conclusion but rather considers the artists and the viewers perception of the art from a neurological perspective. Nor does Kandel suggest that there is a hemispherical bias in the creation and the acceptance of the radical abstraction of this sort of art (and it’s equivalents in architecture, music and literature). The lack of context and coherence, the static, fragmented and 2-dimensional nature of this modern art is meaningful in a way, I believe, that proceeds artists simply exploring new ways of doing art. It seems they were finding an expression that spoke the same language as their left hemisphere.

I will leave it there for now, but we must explore this further as it has implications to mass psychology and the mess we find ourselves in today. One thing you can wonder along with me is about cause and effect. The Marxists4 promoted the deconstruction of things like beautiful art as part of an oppressive demoralizing campaign against the human mind. So was it such efforts that nudged the collective brain toward a left hemisphere bias? Or was the pendulum starting to swing this way by the time of the Industrial Revolution to inspire such left hemisphere deconstructions of relations (family, religion, nationalism, etc) so well executed by Marxist ideology?

Even apart from the Marxist question, what can we identify with in this age with a perspective that is 2-dimensional, reduced to the simplest components, inward and removed from reality?

I will offer my own ideas as we go along, but this is a puzzle, so I can’t give away too much at the outset!

Kandel, E. R. (2012). The age of insight: the quest to understand the unconsious in art, mind, and brain. From Vienna 1900 to the present. New York, N.Y.: Random House.

McGilchrist, I. (2009). The master and his emissary: The divided brain and the making of the Western world. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sorry if you don’t like puzzles and this analogy is irritating. I don’t particularly like the puzzles some are so fond of - the picture of a beautiful landscape with 100 odd pieces of pure blue sky that drives you mad trying to solve while you think you could be spending the time reading a book or going for a nice walk. Besides, it hijacks the family dinning room table for weeks on end and after a number of mishaps, maybe it was the cat, and parts are discovered on the floor, and the sky is never finished (nor that tricky part of the forrest) the whole thing is chucked back in the box for another winter when you have well and truly forgotten what a headache the ordeal was. Hopefully THIS puzzle will not be that sort of experience.

Interestingly there are remarkable similarities between people who don’t have a properly functioning right hemisphere (and thus their left hemisphere is unusually dominant) and people with schizophrenia. The schizophrenic will display many of the same attributes of perception as the left hemisphere. As we go on I’ll touch on more psychopathologies that correlate directly with the perception and behaviour of the left hemisphere - pathologies that can look very much like the patterns of thought and behaviour in our modern world.

Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian.

I’m picking on Marxism because its propaganda so obviously appeals to the left hemisphere’s take on reality and is diabolical in it’s capacity to put the mind into a type of psychosis - more on this later.

This is fascinating. I’ve been interested in mcgilchrist in relation to autism/Asperger’s traits + ADHD. It’s an interesting way of looking at the trans issue too. My very high IQ ASD son who had echolalia (which demonstrates learning extremely efficiently from a decontextualised left brain) and now is trans, which I see as a kind of developmental echolalia of puberty. He is also now a musician creating very mechanical sounding music. So much in this! And there is also a corresponding spectrum of right brain dominant females becoming more prone to and suffering mental illness due to difficulty with left brain processes dominating life.

Very interesting article once again. I wouldn't be caught dead with that Picasso in my house though.